“Però i veleni dello scandalo sono ancora tra di noi,

e creano divisioni che bloccano tutto.”

The poisons of scandal are still amongst us, and they create rifts that separate us.

On December 12, 2012, somebody broke into Gianfranco Soldera’s winery and started pulling taps on barrels and tanks. When the crime scene was discovered the next day, it was a ghastly picture: 16,500 gallons of wine had been drained onto the floor. Five full vintages of hard work, dedication, and investment went down the drain in a matter of hours. This meant utter devastation for the vintner, whose entire livelihood depended on the product of his vines. While this act of wanton vandalism certainly shocked the region, it came on the heels of an even bigger scandal, which some say was the motivation for the vandalism itself.

Gianfranco Soldera criticized other Brunello producers for blending non-Montalcino grapes into their wines and, as a result, had his cellars vandalized.

It was only four years prior that several producers in the region were investigated for allegedly adding illegal grapes to their Brunello blends. This rocked the world of Italian wine and made international news. Italian authorities indicted a group of winemakers and oenologists and investigated winery practices throughout the region. The United States Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) even got involved, refusing to import certain wines that couldn’t be verified as authentic Brunello di Montalcino. By law, Brunello wine must be made from 100% Sangiovese grapes, yet many winemakers were suspected of adding Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot to lend color and softness to a wine that is sometimes sharp in its youth. One of the main whistleblowers, a man who routinely criticized other producers, was none other than Gianfranco Soldera himself, whose winery would soon be vandalized.

Scandal in wine is as old as time. In fact, ever since there were wine regions, there were people trying to play off fake wines as the real thing. Pliny the Elder was a great Roman writer, historian, and drinker who traveled the Roman Empire sampling local beverages. Even Pliny said of famous wines,

“that it is the name only of a vintage that is sold, the wines are being adulterated the very moment they enter the vat.”

Fraud was also rampant in the Colonial era, when wines like Sherry and Port were often diluted by unscrupulous merchants to stretch out their product or faked completely by flavoring water with berry juice, cheap brandy, spices, and even poisonous substances like lead! When there’s a dollar to be made, fraud will rear its head – even in the modern era.

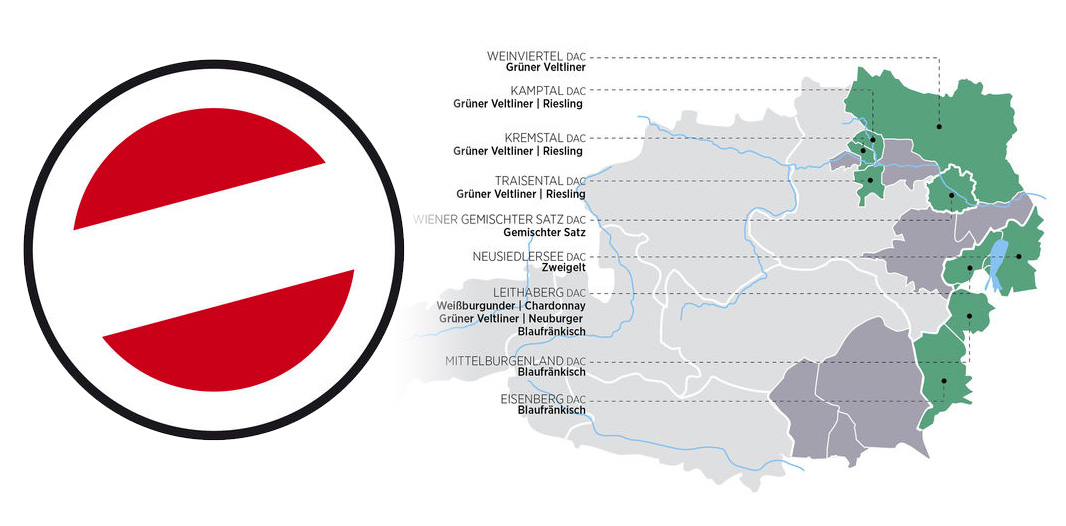

In the 1980s, the Austrian wine industry was rocked by the discovery of diethylene glycol, an antifreeze ingredient, in some producers’ wines. This chemical was used to add viscosity and richness to cheap wines, but it’s a big (dangerous) no-no when it comes to consumption. Fortunately, no illnesses or deaths were linked to the scandal. The Austrian wine industry and the government suffered a huge blow to their reputations and rebuilding proved to be a long-term success. In the wake of the scandal, the Austrian government worked swiftly to raise standards, clamp down on bad winery practices, and ensure every wine was tested before it was released to market. Thirty years later, the Austrian wine industry makes some of the cleanest, most rigorously verified wines in the world and the consumer is better off for it. In this case, out of fraud came a change for the better.

Austria now stands proudly behind its seal of quality, one of the most rigorous wine testing standards in the world. The Austrian flag on the bottle capsule is a guarantee of both origin and testing.

Sometimes the scandal is a bit sneakier but equally damaging to reputations. In 2006 the most famous producer of Beaujolais, Georges DuBoeuf, was convicted by a French court of mixing lower-grade Beaujolais-Villages into a single-village Cru wine. After a hefty fine of €30,000 and a jail sentence for the winery manager who perpetrated the blending, the most damaging punishment fell upon the region of Beaujolais itself. Even if the small producers didn’t perpetrate the blending, they were ultimately the ones who suffered when their best-known producer committed fraud. Beaujolais is still rebuilding its reputation after this incident. The good thing is that they’re making some delicious wines in the process. Beaujolais has revitalized itself with a greater focus on Cru wines from areas like Morgon and Côte-de-Brouilly.

The Bottom Line on Fraud

Scandals hurt the consumer and damage the reputation of other producers in a wine region. While many producers have used fraud to make a few extra dollars, they usually get caught. A government that creates regulation to reduce fraud lays groundwork for a more successful wine industry in the future (just look at Austria!).

What You Can Do

As consumers, we should still be concerned about fraud, especially in an era of unprecedented choice. There are more wine labels available for purchase today than ever before. How can we trust that the label on the bottle is telling us the truth?

Buying wine from producers and regions that have a strong interest in their reputation is the best way to guarantee honesty. Someone selling a $5 bottle of wine might be somewhat interested in their reputation, but only as far as they’re able to move units and keep costs down. A producer from a controlled region who harvests by hand and produces a limited number of bottles a year lives and dies by their reputation.

Terms to look for

Seek out wines that are transparent about their production methods and that take pride in them; they might include the following labeling terms:

- Hand-Harvested: brands that harvest by hand intentionally spent money and time to make sure human hands brought the grapes safely from the vineyards to the press

- Single Vineyard: this wine likely comes from a smaller area that has developed a reputation for quality wine, which suggests that the producer has a vested interest in that reputation

- Old Vines: (old bush vines) planted across many parts of Australia, Spain, Southern France, and California, are harder to harvest by machine, and a producer making this wine is spending a greater amount of time, money and effort to make it because they care about this vineyard

- No Additives: beyond sulfur, which both occurs naturally in wine and is added during fermentation and bottling to keep a wine preserved, additives like Mega Purple and Velcorin are used in cheaper wines to make their product look and taste better or have longer shelf life; these wines aren’t fraudulent, but a producer who elects not to use them typically cares about the vineyard source and about transparency in winemaking

- Biodynamic: a producer who has taken the immense effort to certify his vineyard as biodynamic most likely cares about the land and is unwilling to take shortcuts in the wine production process

- Organic: this is not a guarantee against fraud, but a level of care for the land and the vine that helps you trust a producer’s intentions to make something pure

- Ingredients List: a producer who lists her ingredients is showing you that she isn’t using shortcut additives to make the wine taste better; ingredients are going to increasingly become a way for us to evaluate the purity and transparency of wine in the future

None of these methods provide any actual guarantee against fraud and even great regions and producers can be plagued by this issue. But, knowing who makes your wine and being able to trust them is the best guarantee you have.

It’s our hope that honesty becomes the norm and that scandals grow fewer and further between!