Wine isn’t a bedrock historical tradition in the United States, as in Italy or France, but not for lack of trying. Old World regions like Italy, France, Portugal, Spain and even Switzerland have been doing the wine thing for thousands of years. Much like cheese making or curing meats, making wine was how ancestral Europeans preserved nutritional value between growing seasons. Over time, the wine culture of Europe developed in tandem with cuisine, through centuries of changing traditions… No matter how you look at it, American wine is growing up differently, but that’s not necessarily a bad thing.

Despite Europe’s head start, American wine traditions are happening quietly all around us. While wine may still not be linked closely with regional culinary traditions, the seeds of new tradition are being sewn all over America. You just have to know where to look.

5 American Wine Traditions Worth Keeping

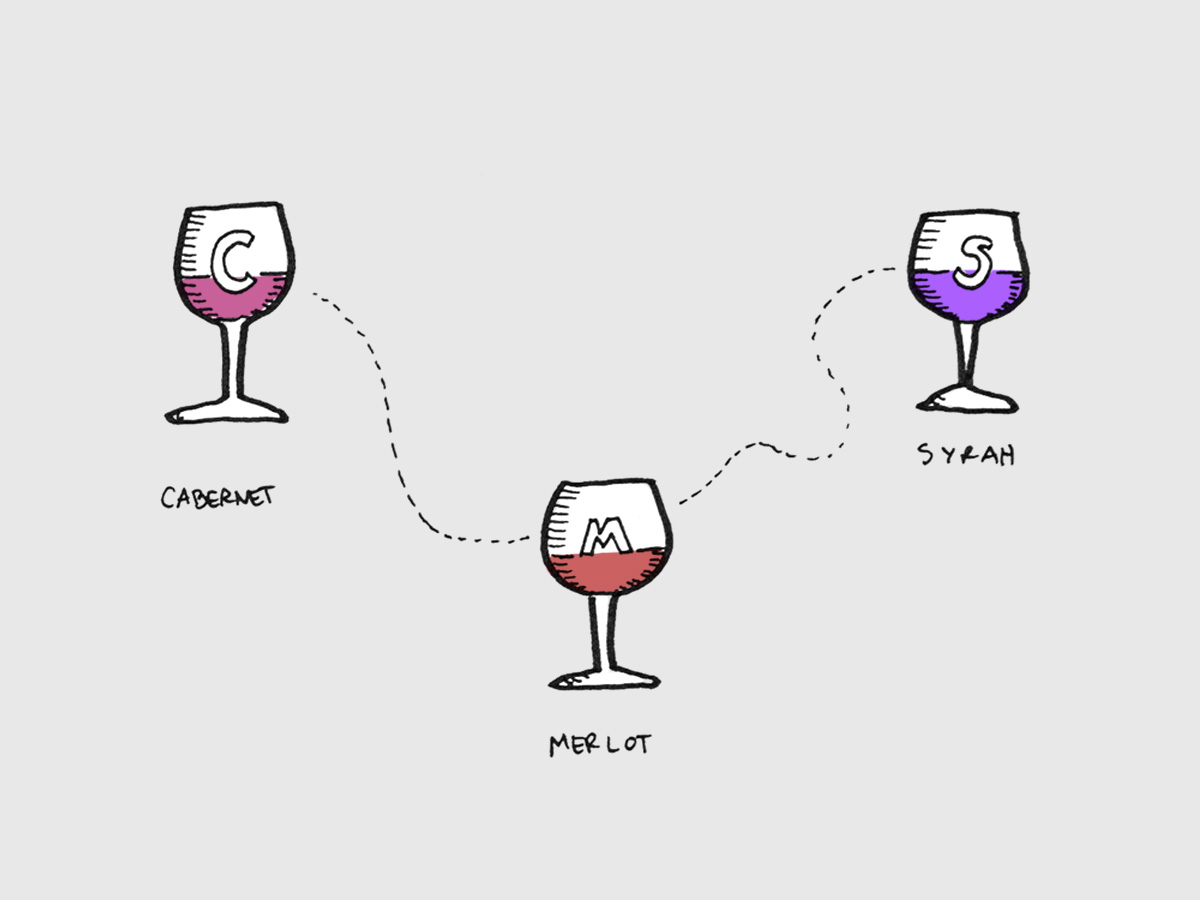

The CMS Blend from Washington State

Wine blends are not as freeform as one might think.

Traditional European wine blends began of practical farming necessity, and the traditions most of these blends are long-standing. For example, no region traditionally blends Sauvignon Blanc with Chardonnay, and so seeing this combination from anywhere in the world is unlikely.

Many popular wine blends are modeled after French tradition, most notably (for red wines) the Bordeaux Blend and the Southern Rhône/Grenache-Syrah-Mourvedre (GSM) blend. However, one American region is creating their own tradition with a delicious new blend: the Cabernet-Merlot-Syrah or “CMS” blend. Washington state produces a wealth of the three varieties and several producers have started to blend them together to great success.

While it was common practice in the middle part of the 19th century for Bordelaise and Burgundian winemakers to add Syrah and other southern french grapes to increase body and fruit in cold vintages, the practice has been illegal since at least the 1930s. No one advertised this practice then, and certainly French winemakers don’t use it today. The re-imaging of the CMS blend for the modern drinker is a uniquely American idea.

American Oak in Full-Bodied Red Wines

Great wines made with American oak.

Unbelievers of American oak go into great detail about the differences between the two oak species (European Quercus Robur versus American Quercus Alba); they say European oak posses thinner grain (for smoother tannins) and the oak lactone flavors are more subtle. Certainly, the cost per-Barrel (about $1500 for a 300-liter barrel) is higher, making it sound like the European oak is empirically better. Of course, really, as with much in wine, a firm answer on which oak is superior for aging wine is a subjective matter of taste.

We’d agree, some wines (especially Pinot Noir and Chardonnay) do need the soft hand of European oak to create a nuanced expression, but others grapes (like Tempranillo and Merlot) taste awesome when tickled with American oak, which tends to have a more savory flavor that these grapes jive with more successfully. American oak has many benefits, including decreased environmental and monetary cost, as well as imparting oak aromas for far more uses than European oak. The fact that American oak is native to the continent may make it one of our greatest traditions!

Truth-In-Labeling of Oregon Chardonnay and Pinot Noir

Oregonian idealism (“Oregonianism”) is finally paying off.

The green wave of idealism has been woven deep into the culture of Oregon. When you buy an Oregon wine labeled “Pinot Noir” it is required to contain at least 90% Pinot Noir. Most of the rest of the nation (including California, our largest-production state), requires only 75% of a grape for a labeled single-varietal wine. As American consumers demand more truth-in-labeling, we should look to Oregonians who are leading the way. Just so you know, the certification clause only affects Pinot Noir, Chardonnay and Pinot Gris and not other varietal wines in the state.

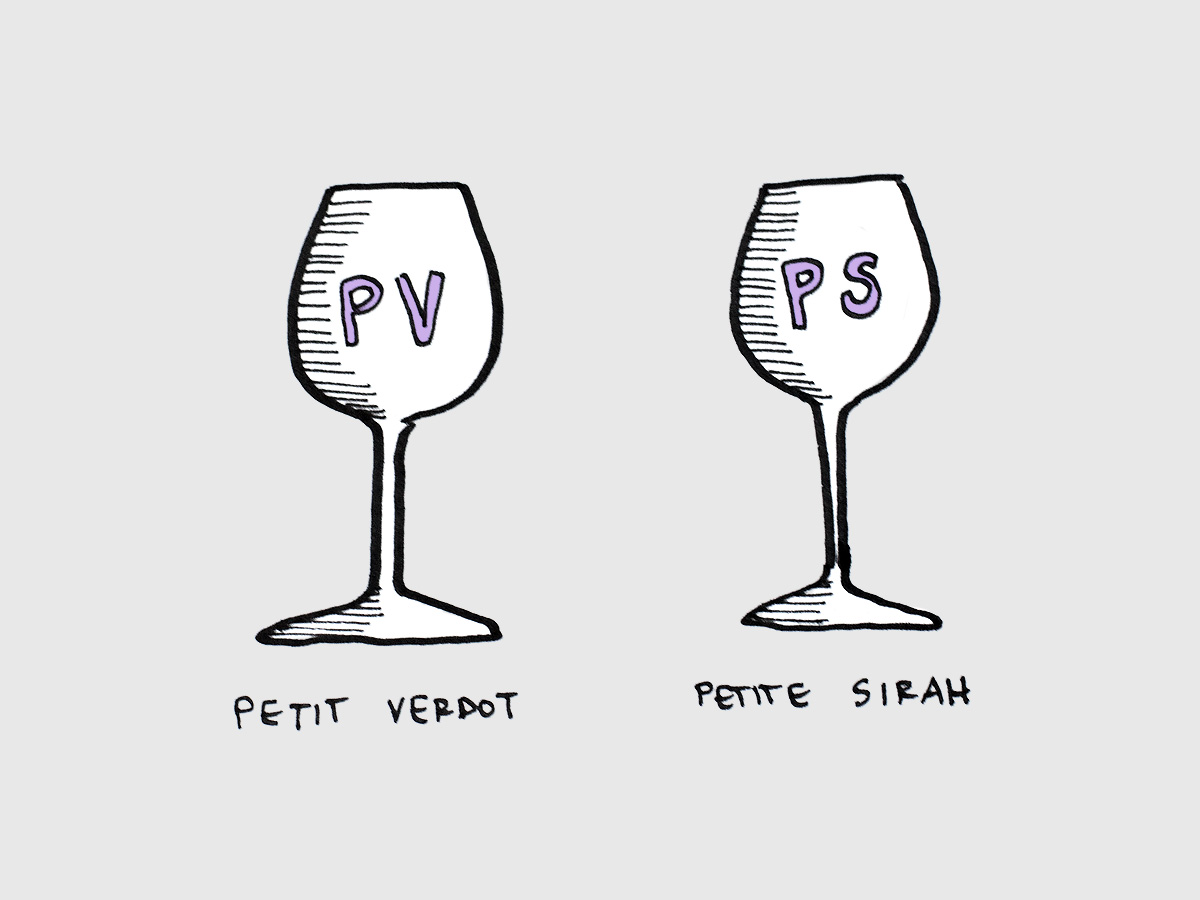

Single-Varietal Petit Verdot and Petite Sirah From California and Washington

These French varieties are actually quite rare in France.

Small-berried Petit Verdot usually composes no more than 2%-3% in a Bordeaux Blend, adding tons of backbone (acid and tannin). The only time you’ll taste Petite Sirah (a.k.a. Durif) is if you chance upon it as usually a small blending component in wines throughout southern France.

In America, both Petit Verdot and Petite Sirah are much more commonplace, because they’re proven great alternatives for big red wine lovers. Both are often accompanied with aggressive, long-term aging in high-toast oak.

Petit Verdot: In Bordeaux’s atlantic maritime climate, Petit Verdot often struggles with ripening and thus is never a large part of the Bordeaux blend. However, with love from the Washington and California sunshine, the variety reaches entirely new heights with jet-black, inky intensity, and aromas focused on juicy black fruit (black plum, blackberry, and blueberries) as well as purple floral notes (violets, lavender). Huge body, fresh acid, and powerful tannins are all hallmarks of Petit Verdot.

Petite Sirah: The largest plantings of Petite Sirah are in California. Much like Petit Verdot in the glass, the grape is known for a more sun-dried, darkly-fruited nature (dark mission fig, prune, pomegranate grenadine, and blackberry jam). While equally as intense in terms of body, often Petite Sirah has slightly softer tannins and acid than Petit Verdot.

Innovation and New Grape Varieties

Will America be the site of the next great wine variety?

The vineyard at Popelouchum (“pope-loh-shoom”) is trying to breed a whole new set of particularly American varieties. The vineyard’s owner, Randall Grahm is one of the most standout, enigmatic names in American wine. He created Bonny Doon Vineyard and sold three successful household brand names in wine (Big House, Pacific Rim and Cardinal Zinfandel) to make his bones, but Grahm’s latest project is the stuff of iconoclasts, and borderline insanely risky. Popelouchum, an experimental vineyard-farm, sits directly atop the San Andreas Fault close to an old limestone quarry. Grahm intends several longterm goals for the site, one of which is creating “10,000 new wine varieties.”

While, in reality, this endeavor is less crazy than it might sound, it’s still an enormous new undertaking with no clear business case. Historically, in the Old World, grapes would grow often from seed (instead of clones) which creates a greater opportunity for mutations and natural cross-breeding to occur. When nature is in the driver’s seat, the unpredictable can yield magical results, including the creation of new wine varieties. The worlds most popular grape, Cabernet Sauvignon, is a natural crossing of Cabernet Franc and Sauvignon Blanc.