Some things (wine, clothes, people…) improve with age and others do not. Maybe you have a t-shirt that’s 10 years old that looks better and better with each wash cycle. Some of us believe that the secret to true success is to slowly cultivate a life surrounded by classics. It becomes a simple question: “Will this endure the test of time?” Suddenly, choosing the right thing becomes much easier and, the best part is, you won’t regret it later.

So the question is, how does one identify future classics in wine?

As it happens, most wines (the ~95%) aren’t meant to age, so you’ll discover that finding an age-worthy wine is a bit more challenging; almost akin to finding well-made clothes. So…

If most wines only last a couple of years, what makes a wine worthy of cellaring 10–20 years? Let’s discuss the primary traits of age-worthy wines and what considerations to make for collecting age-worthy wines.

Wines with Structure

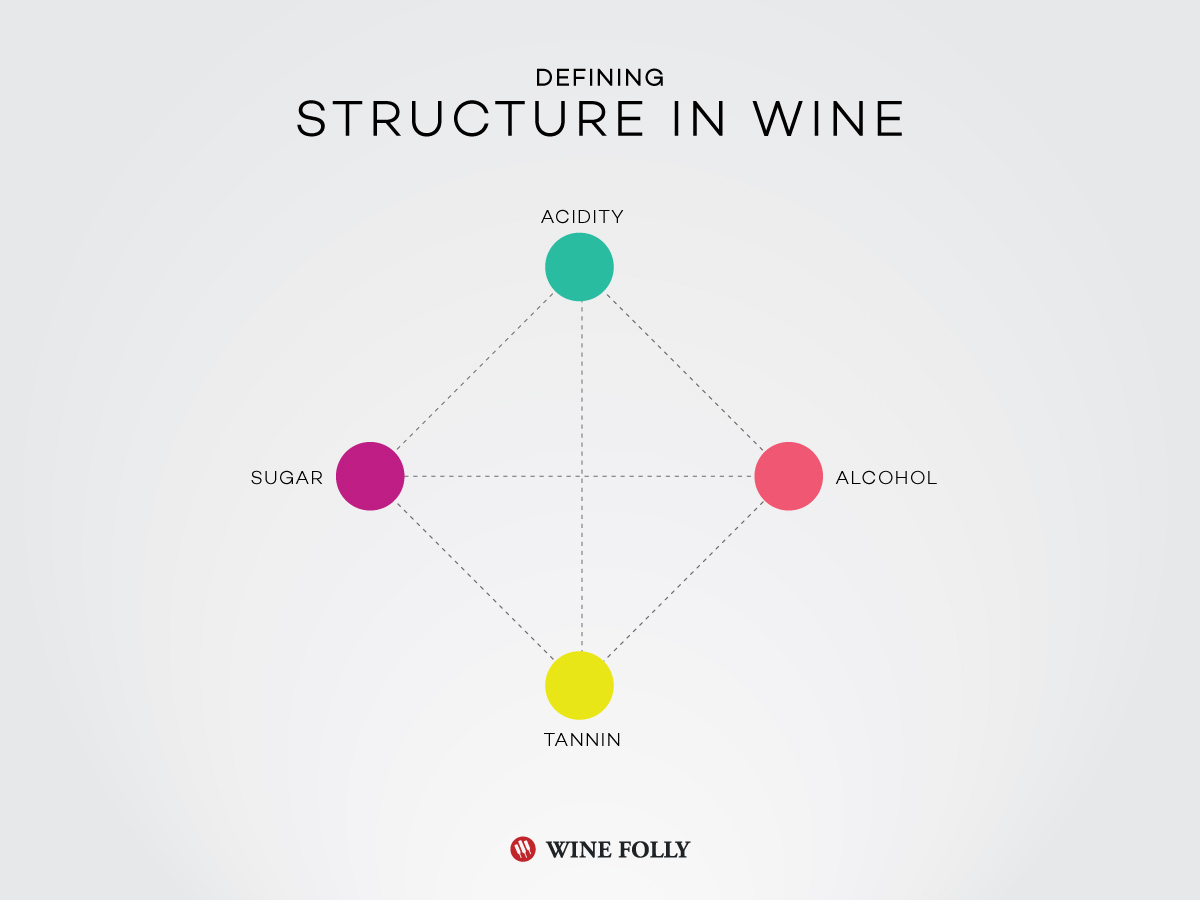

Finding wines that will improve over time requires that you pay attention to a wine’s structure. What is structure? It’s the taste attributes found in wine that act as natural preservatives:

-

Acidity

Wines lose acidity over time, so it’s important that the acidity be moderately high.

-

Polyphenols (Tannin)

The polyphenols in wine stabilize things like color and flavor. Thus, wines with moderate tannin (from both oak or grape) have a longer runway to age.

-

Sweetness

Sugars have been used as a fruit preservative (jam) for a very long time. The same ideology behind fruit preserves also applies to dessert wines and wines with high sweetness levels.

-

Alcohol level

Alcohol is one of the primary catalysts that causes wine to break down. Strangely enough, it also acts as a stabilizer in higher amounts (e.g. fortified wines and some dry wines with >15%+ ABV). So you either want lower balanced alcohol levels or high alcohol levels.

-

Low Volatile Acidity

Acetic acid is detrimental to age-worthiness in wine. Avoid wines with VA levels around 0.6 g/L and above.

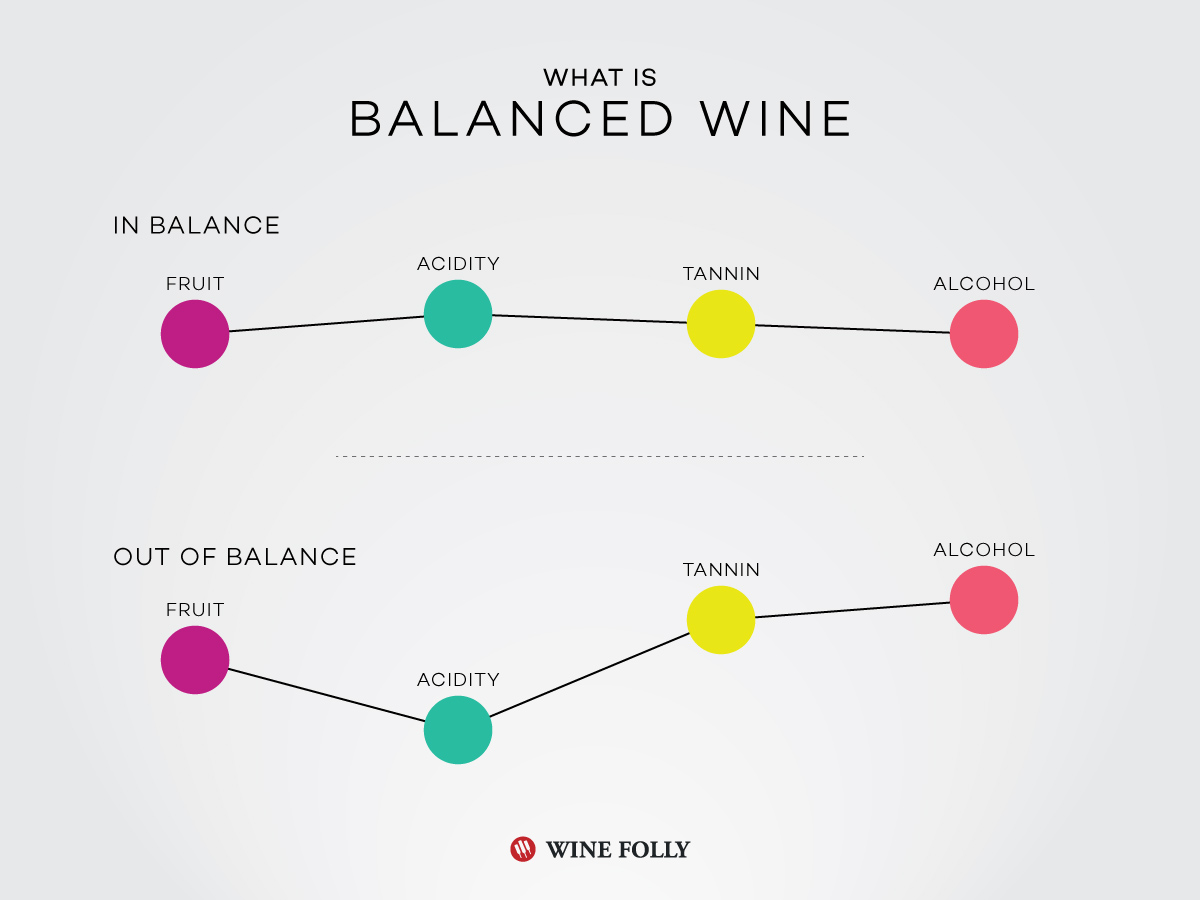

Balance

After structure, look at balance. Are all the attributes of the wine in balance with one another? If a wine has tons of tannin, acidity and moderate alcohol (maybe around 12%–13.5% ABV) but has no fruit then it’s not really in balance.

Producer

Who made the wine? Before buying, look into the producer’s history. Ideally, grapes are grown on the producer’s estate and the winery has a track record of solid winemaking for 15+ vintages. Of course, there are many well-made age worthy wines made by producers who don’t fit this profile (and vice versa), so don’t let this alone deter you. The biggest red flags for producers would be inexperienced winemakers who don’t have a scientific understanding of enology at the helm. These wines are no problem upon release but subtle flaws will become exacerbated with age. Another deterrent would be white label wine brands; these wines are usually made to drink now and will not increase in value.

On Buying Dry Red Wines

Dry reds are the most collected of all wines, not necessarily because they age the longest, but because it is a delight to drink old dry red wine. Beyond seeking an ideal basic structure in the wine, you want to make sure that the wine has ample runway which means moderately high acidity. One way to pay attention to the acidity is to feel the finish. Wines usually have a long tingly aftertaste from the acidity paired with residual fruit flavors. If you feel just the dry astringency of tannin, then the wine might be a bit out of balance (too much tannin, not enough acidity).

Somewhat over-simplified overview of red wine aging potential:

- Nebbiolo ~20 years

- Aglianico ~20 years

- Cabernet Sauvignon ~10–20 years

- Tempranillo ~10–20 years

- Sangiovese ~7–17 years

- Merlot ~7–17 years

- Syrah ~5–15 years

- Pinot Noir ~10 years (longer for Bourgogne)

- Malbec ~10 years

- Zinfandel ~5 years

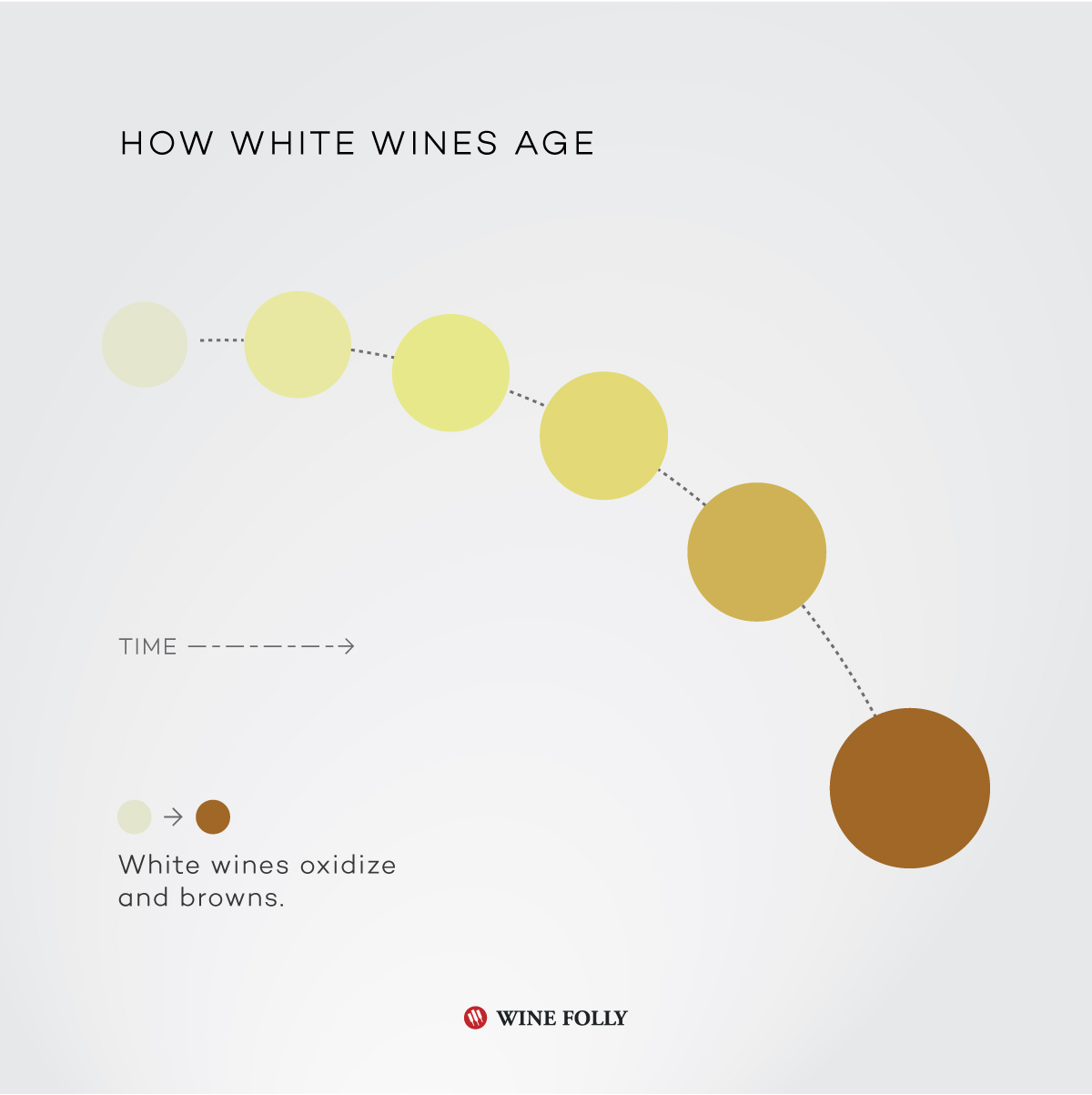

On Buying Dry White Wines

White wines generally have a shorter timeline for aging. This is because they do not have the same structural components (tannin) as red wines.

Certainly, there are a few exceptions to this (such as orange wines), but for the most part, white wines rarely last past 10 years.

There are 3 factors to look for with age-worthy dry white wines: acidity, a touch of phenolic bitterness (see below) and, in some whites, oak tannins. White wines aged in oak, such as Reserva Rioja Blanco and Chardonnay, have added polyphenols from the oak.

And, since polyphenols help mitigate chemical reactions that break down wine over time, oaked whites typically have a longer timeline. Be extra sure that the acidity is high to keep wines from getting flabby with age.

What is phenolic bitterness? Bitterness in white wines can come from 3 primary places: from a specific aroma compound (it’s called terpenes and it’s found in aromatic white wines like Riesling), from using slightly underripe grapes, or from longer skin contact during winemaking. While most of us detest bitter flavors in white wines, this trait does add enough polyphenols to create a longer runway on white wines. As long as the wines aren’t overly bitter and have good acidity, you can expect the wine to age moderately well.

Somewhat over-simplified overview of white wine aging potential:

- White Rioja ~10–15 years

- Chardonnay ~10 years (longer for Bourgogne)

- Trebbiano ~8 years

- Garganega ~8 years

- Sémillon ~7 years (longer for Bordeaux)

- Sauvignon Blanc ~4 years

- Viognier ~4 years

- Muscadet ~3 years

- Pinot Gris ~3 years

On Buying Sweet Wines

Sweet wines and dessert wines have some of the longest runways to age of all wines because of the high sugar levels acting as a preservative. Generally speaking, red dessert wines will last longer than whites. The real secret to finding age-worthiness in this category is acidity (again!). When you taste a sweet wine to check for its cellar-worthiness, you’ll be surprised how dry it tastes for the level of residual sugar. For example, a good Spâtlese Riesling will have somewhere around 90 g/L RS and taste only off-dry, it will also likely have ripping high acidity and a touch of bitterness (phenolic bitterness) on the back mid-palate.

Somewhat over-simplified overview of sweet wine aging potential:

- Recioto della Valpolicella ~25–50 years

- Hungarian Tokaji Aszu ~20–30 years

- German/Alsatian Riesling ~15–25 years

- French Sauternes ~15–25 years

On Buying Fortified Wines

Fortification is a practice of adding a neutral distillate (usually grape brandy) to preserve a wine. Of all wines, these wines last the longest, and some continue to improve in taste as they age in the producers cellars for 200+ years. Of course, some fortified wines aren’t meant to age, such as Ruby Port which is made and bottled in a way that makes it impossible to cellar for very long. Generally speaking, the fortified wines that have spent the longest time in wood will age the longest. The time spent in wood continually exposes the wine to small bits of oxygen which causes the color to drop out of red wines (and white wines to brown) but it actually stabilizes the taste. It was a surprise tasting of an Australian Tawny that had been sitting opened in my grandmother’s cellar for nearly 20 years and it still tasted vibrant and delicious.

Somewhat over-simplified overview of fortified wine aging potential:

- Tawny Port ~150 years (when aged in winery)

- Madeira ~150 years

- Vintage Port ~50–100 years

- Banyuls ~50–100 years

- Sherry ~75 years

- Vin Santo ~50 years

- Muscat based fortified wines ~50 years

How Red Wines Change

Understand how red wines change in taste as they age. We tested a single vineyard Merlot wine over a period of nearly 30 years and have some very interesting notes on the evolution of collectible wines.