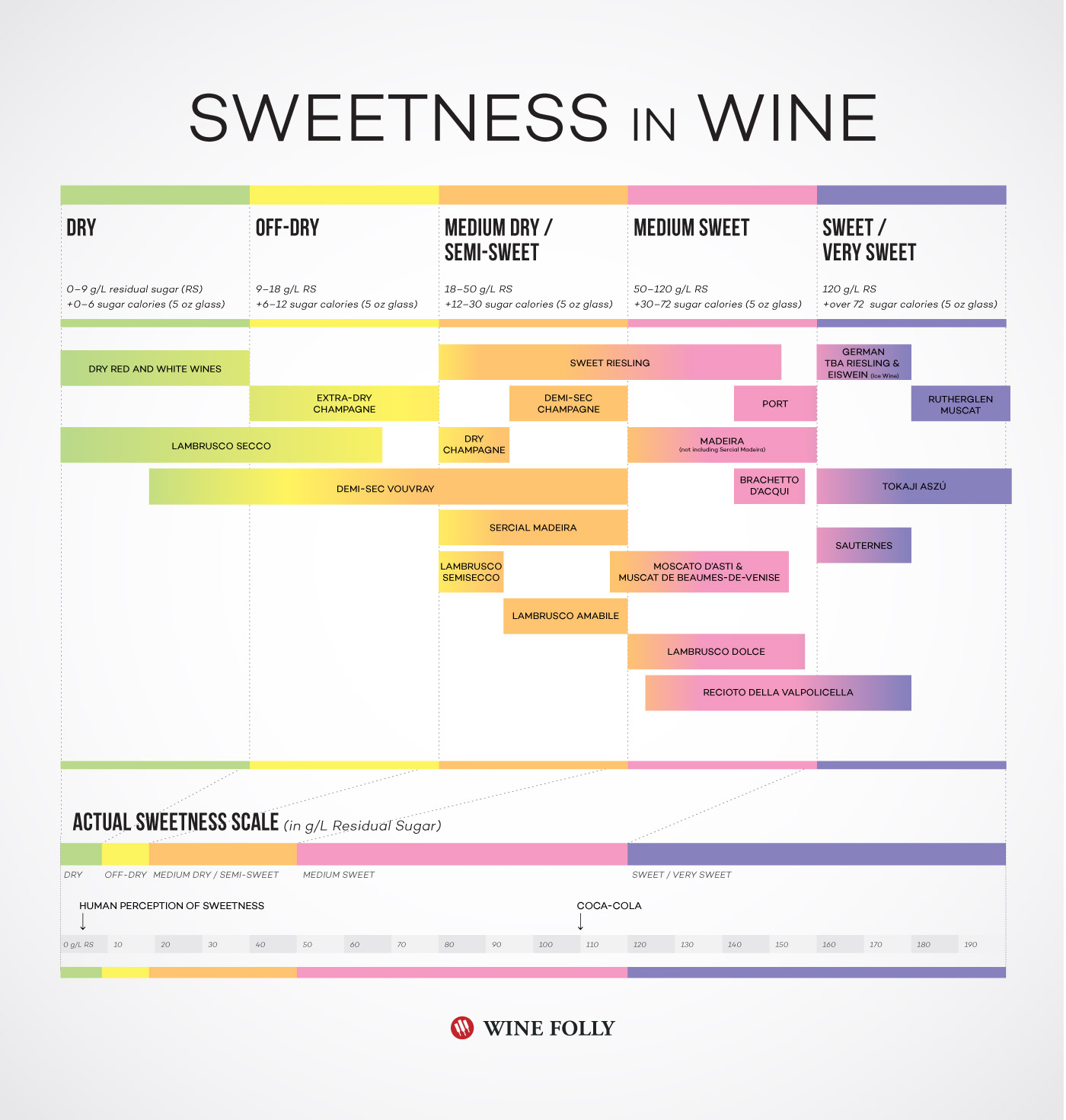

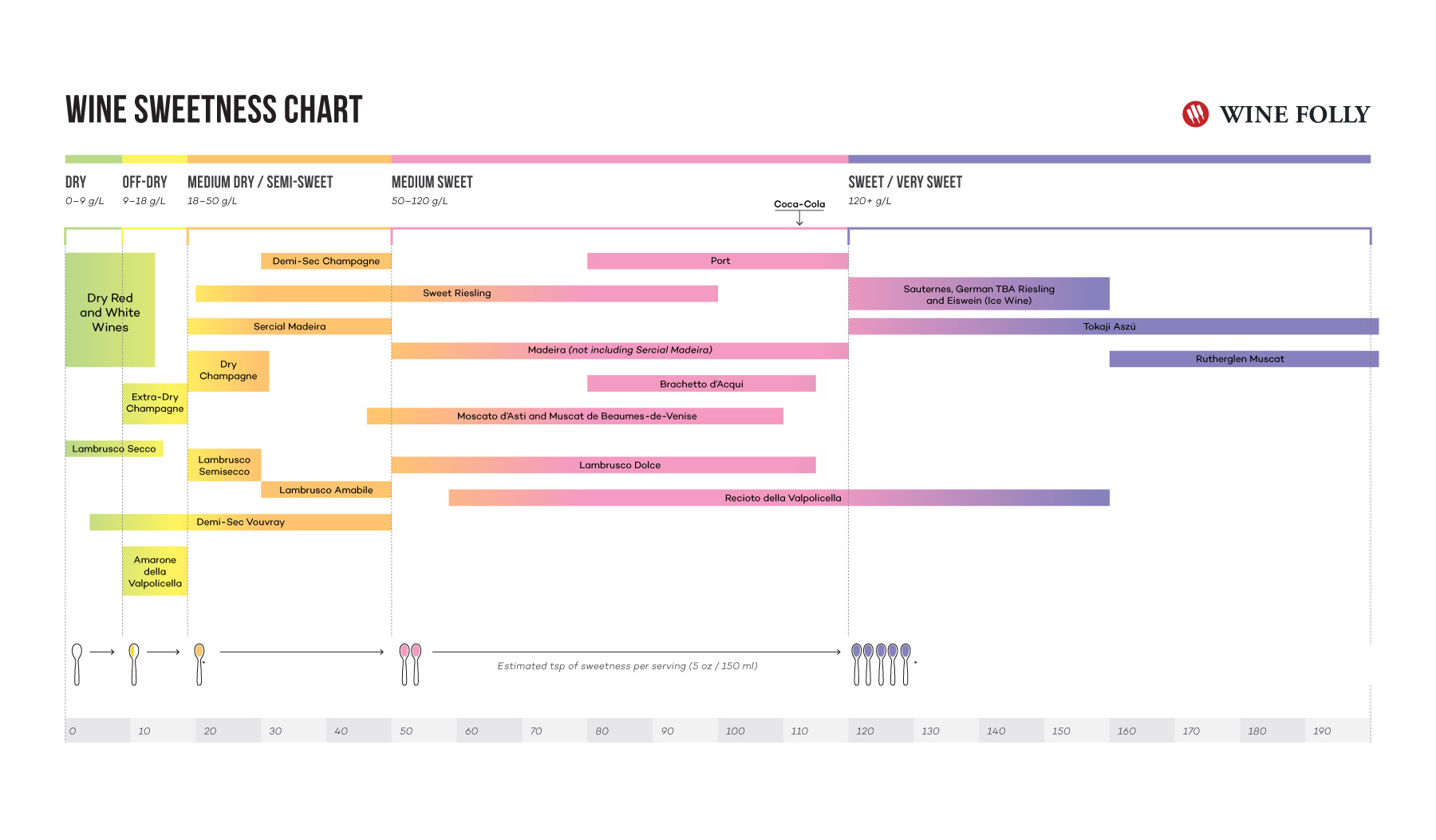

We charted the sweetness in wine from bone-dry to richly sweet. Sweetness (and how we discuss it) is one of the most commonly misunderstood topics in wine, but with a little clarification you can taste and talk like a pro.

We’ll hopefully resolve any confusion for you around terminology, and then give you a look at actual sweetness levels of various wines. You might be surprised to notice that many sweet-tasting wines are less sweet than they seem and many dry-seeming wines are more sweet than you might realize.

Wine From Dry to Sweet

This chart identifies wines based on their sweetness level. You’ll note that occasionally a wine will not entirely fit within the bounds shown above because variations in production style.

Terms to Know

- Residual Sugar (RS) This is the level of glucose and fructose (grape sugars) that are not converted into alcohol during fermentation. RS is most commonly measured in grams/liter.

- Dry Dry = not sweet. The EU Commission Regulation has indicated that dry wines with moderate acidity may contain no more than 9 g/L of residual sugar, excepting when acid is over 7 g/L as well. The major exception to this is Champagne-style wines, which for some reason use the term “dry” for relatively sweet styles of wine. But hey, nobody ever said this wasn’t complicated…

Why do some dry wines taste sweet?

Let’s say you buy a bottle of Dry Gewürztraminer, and the winemaker says it’s 100% dry. Yet, when you take it home and give it a taste, it tastes sweet! What’s going on?

The confusion around sweet and dry is caused by aromas, i.e. what our nose tells us about a wine. When you’re smelling aromas found in very ripe wines, like, for example, blackberry jam or banana yogurt, it’s because you’re used to associating these smells with actual sweet foods. Your brain links the aroma with its usual related taste sensation, outside of the context of wine, and so you say a wine is sweet, when you haven’t yet even taken a sip!

- Pretty much all quality red table wine sold in the US is dry, with notable exception of very high bulk production wines that will often obscure any faults with a few (less than 10) grams of sugar, as well as mevushal wines, such as Manischewitz (estimated around 170 g/L RS!).

- For white wines, pretty much only three regions in Europe traditionally make high quality off-dry or “harmoniously sweet” table wines: the Loire Valley (for Chenin Blanc), Pinot Gris, Riesling, Gewurtztraminer, and Muscat from Alsace in France, as well as much of the Riesling from Germany (although, there is also dry German Riesling).

Sweet Pinot Grigio from Italy? Nope. Sweet Sancerre from France? Nope. Sweet Albariño from Spain? Nope. Many European wine laws mandate that wines from a region be less than 4 grams per liter, thus making them dry by law.

If you dig around the US Federal Code of Regulations for wine labeling you’ll discover that there are no requirements or designations for dry wine in America. So instead, we derived the basic definition of sweetness and dryness (in the above chart) from the EU Commission Regulation with 2 slight modifications.

Our mouths are not that smart

Acidity and bitterness reduce our perception of sweetness in wine.

Our perception of sweetness is affected based on structural components of a wine. Wines with elevated acidity and bitterness will mask the taste of sweetness. Think of it like lemonade. You don’t want to drink the highly acidic lemon juice on its own, but in the right balance with sugar you get tangy sweet-and-sour refreshment.

In fact, many dry acidic wines (such as dry German Riesling and dry Furmint from Hungary) permit proportionally higher residual sugars when the acidity is above a certain level, because they’ll still taste dry. By the way, the sweetness is almost always derived from leftover, natural grape sugars, rather than the addition of processed sugar (phew!).

You can learn to identify nearly undetectable sweetness in mostly dry wines. Just build a repertoire in your memory of wines you’ve tasted that you know to contain residual sugar. For example, almost all sparkling wine contains low, but perceptible, levels of sugar. “Brut” wines can be up to 12 g/L RS in most cases, but because of the super aggressive acid these wines often have, the sweetness presents more as mid-palate weight and texture, than the candy-like sense we usually think about with sweetness. In fact, sugar is added to sparkling wines on purpose because otherwise they’d be too tart and screechy for most people’s taste.

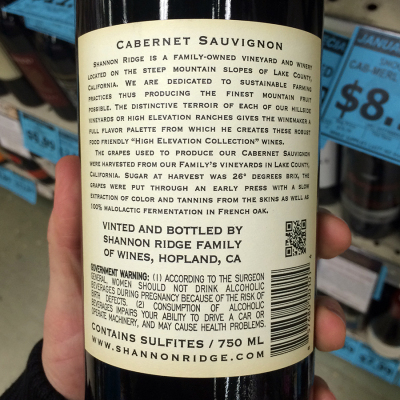

Why aren’t wines labeled with sweetness indications?

Alcohol is a controlled substance (it’s not considered a food) which means that alcoholic beverages (wine, beer, spirits, etc) aren’t required to label nutritional information including sweetness. It does make it hard to identify a wine’s basic characteristics (e.g. how sweet is this wine? how acidic is this wine? how many calories per glass? etc). However, you’ll find that many quality wine producers do provide technical information about their wines online. All you need to do is learn how to read wine tech sheets to determine the sweetness level.

Alcohol is a controlled substance (it’s not considered a food) which means that alcoholic beverages (wine, beer, spirits, etc) aren’t required to label nutritional information including sweetness. It does make it hard to identify a wine’s basic characteristics (e.g. how sweet is this wine? how acidic is this wine? how many calories per glass? etc). However, you’ll find that many quality wine producers do provide technical information about their wines online. All you need to do is learn how to read wine tech sheets to determine the sweetness level.

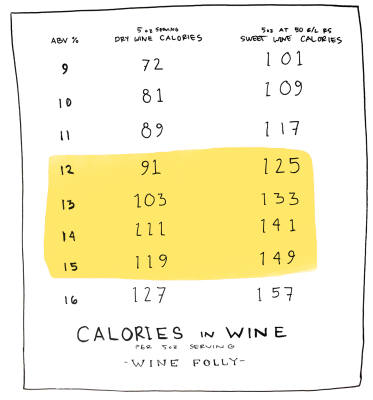

Yes, wine has calories…

Alcohol has 7 calories per gram. Thus, wines with higher alcohol contain more calories. Find out exactly how many calories you’re drinking.