Want to start a wine cellar? Believe it or not, choosing the right bottle closure might be just as important as what’s inside. Dr. Andrew Waterhouse, professor of Enology at UC Davis, explains the importance of wine corks and the aging process.

Corks Seal a Wine’s Fate:

Aging Wine in Natural vs. Synthetic Closures

Most foods are best when they are as fresh as possible. The exception to this rule is the many wines that require some aging to reach their optimal taste. Winemakers know this and work to control the aging process, including decisions they make about how to bottle their product.

Aging and Oxygen

One aspect of aging is the reaction between fruit acids and alcohol. This process reduces sourness in the wine, but it’s particularly important for very tart wines, like those originating from cold climates.

The complex oxidation process is the second aspect of aging. When oxygen interacts with wine, it produces numerous changes, ultimately yielding an oxidized wine with a nutty aroma. This is a desired taste for sherry styles, but quickly compromises the aromas in fresh white wines.

However, the oxidation process provides benefits along the way to that unwanted endpoint. Many wines develop undesirable aromas under anaerobic – no oxygen – conditions; a small amount of oxygen will eliminate those trace thiol compounds responsible for the aroma of rotten eggs or burnt rubber. Oxidation products also react with the red anthocyanin molecules from the grapes to create stable pigments in red wine.

A bottle’s seal will directly affect how much oxygen passes into the wine each year. That will directly affect the aging trajectory and determine when that wine will be at its “best.”

Stick a Cork in It?

Glass is a hermetic material, meaning zero oxygen can pass through it. But all wine bottle closures admit at least a smidgen of oxygen. The actual amount is the key to a closure’s performance. A typical cork will let in about one milligram of oxygen per year. This sounds like a tiny bit, but after two or three years, the cumulative amount can be enough to break down the sulfites that winemakers add to protect the wine from oxidation.

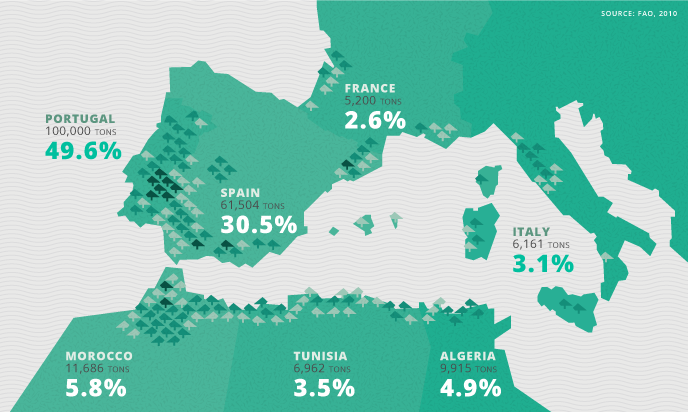

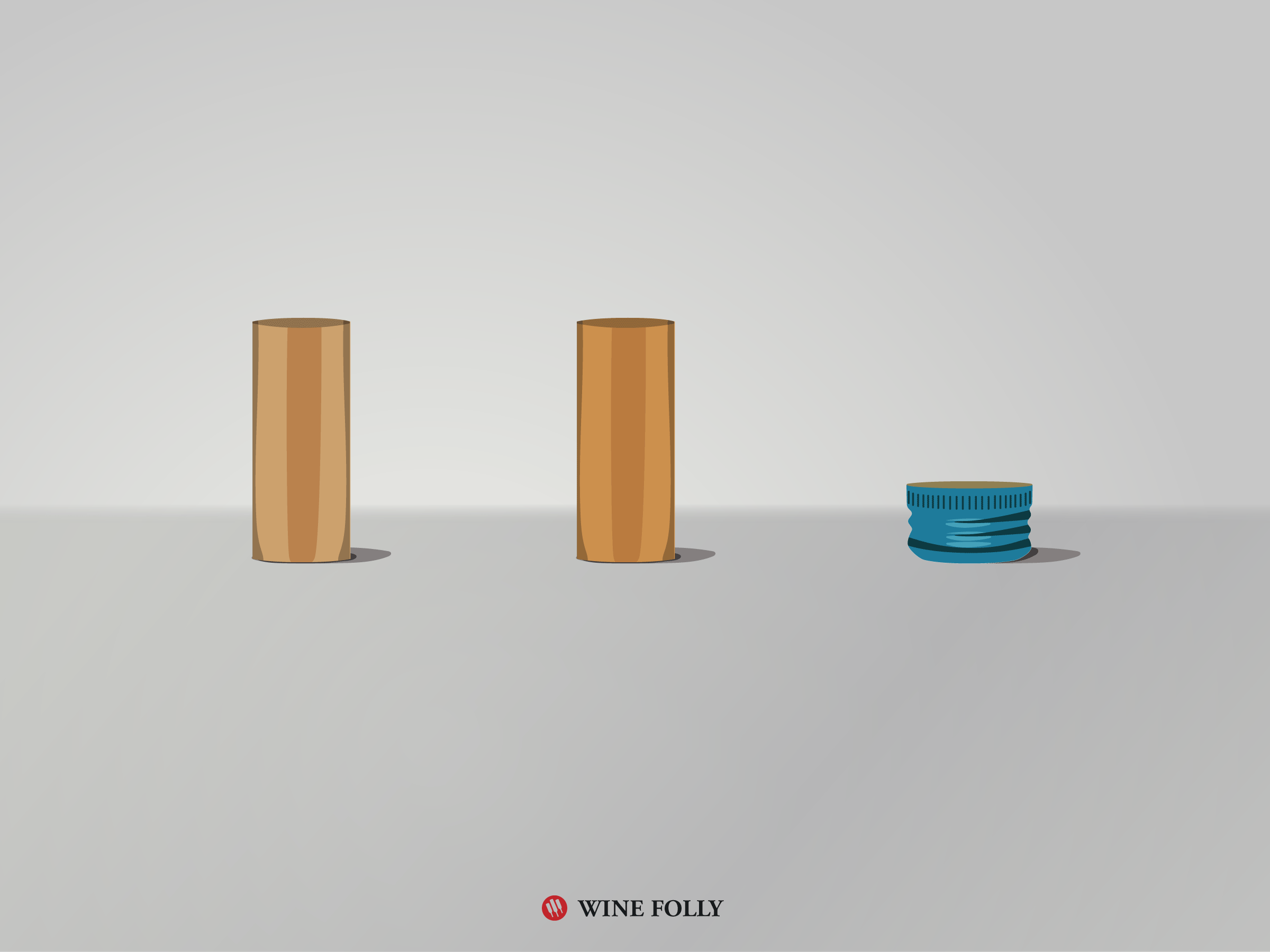

There are three major closure options available: natural cork and technical cork (its low-budget counterpart made of cork particles), screwcap, and synthetic corks. Natural cork closures emerged approximately 250 years ago, replacing the oiled rags and wooden plugs that had previously been used to seal bottles. It created the possibility of aging wine.

Until 20 years ago, natural corks were the primary option for high-quality wine. It’s produced from the bark of the tree, and harvested every seven years throughout the life of a cork oak tree, Quercus suber. The cork cylinder is cut from the outside to the inside of the bark.

A small fraction of corks, 1–2% today, end up tainting the wine with a moldy smelling substance, trichloroanisole (TCA). This TCA is formed through a series of chemical reactions within the bottle: chlorine from the environment reacts with the natural lignin molecules in the woody cork to produce trichlorophenol, which is then methylated by mold.

TCA has one of the most potent aromas in the world – some people can smell as little as two parts per trillion in wine. So, in every eight cases of wine, one or two bottles will smell like wet cardboard or not taste their best. This is why restaurants let you taste the wine before pouring – to let you judge if the wine is tainted. A 1% failure rate seems high in today’s world.

Plastic Fantastic?

Synthetic corks are made from polyethylene, the same material in milk bottles and plastic pipes. After years of research and development, these corks now perform nearly as well as the natural version, with three exceptions: they have no taint, they allow a bit more oxygen to pass through, and they are very consistent in oxygen transmission.

Their consistency is a significant selling point for winemakers, as the wine will have a predictable taste at various points in time. Winemakers can tweak the wine’s oxidation rate by choosing from a range of synthetic corks with different rates of known oxygen transmission.

Screwcaps consist of two parts: the metal cap and the liner inside the top of the cap, which seals to the lip of the bottle. The liner is the critical component that controls the amount of oxygen entering the wine. When screwcaps were first used on jug wine, there were only two types of liners available. However, today, multiple companies are competing to offer their take on the optimal rate of oxygen transmission, as well as to replace the tin used in one of the traditional liners. The standard liners admit either a bit more or a bit less oxygen than good natural corks. Screwcaps, being manufactured, are also very consistent.

Is There an Optimum Wine Closure?

The performance of the manufactured closures, made with 21st-century technology, is excellent. Generally, they approximate our expectations, based on over two centuries of experience aging with natural cork closures.

For the regular wine you might purchase for dinner this weekend or to keep for a year or two, any of these closures are perfectly good, while the manufactured closures avoid taint. Your choice is more a matter of preference for opening the bottle. Do you prefer the convenience of twisting off the cap, or would you rather enjoy the ceremony of removing the cork?

For extended aging, however, the only closure with an adequately long track record is natural cork. So to be safe, that is the closure to choose. Once we have solid long-term evaluations of synthetics and screwcaps, it will be possible to judge their suitability for extended aging, such as more than ten years.

Over the centuries, winemakers have consistently leveraged new technology to enhance their products, from oak barrels and bottles to modern crushing and pressing equipment and micro-oxygenation. While manufactured closures have some key advantages, it is proving challenging to displace natural cork due to its centuries-old tradition, albeit with a few problems, and its connection to the natural environment.