Learn how to taste wine with four basic steps. Sommeliers practice the following wine-tasting tips to refine their palates and sharpen their ability to recall wines. Even though pros use this method, it’s actually quite simple to understand and can help anyone improve their wine palate.

Anyone can taste wine; you only need a glass of wine and your brain. There are four steps to wine tasting:

- Look: A visual inspection of the wine under neutral lighting

- Smell: Identify aromas through ortho-nasal olfaction (e.g. breathing through your nose)

- Taste: Assess both the taste structure (sour, bitter, sweet) and flavors from retronasal olfaction (e.g. breathing with the back of your nose)

- Think/Conclude: Develop a complete profile of a wine that can be stored in your long-term memory.

How to Taste Wine

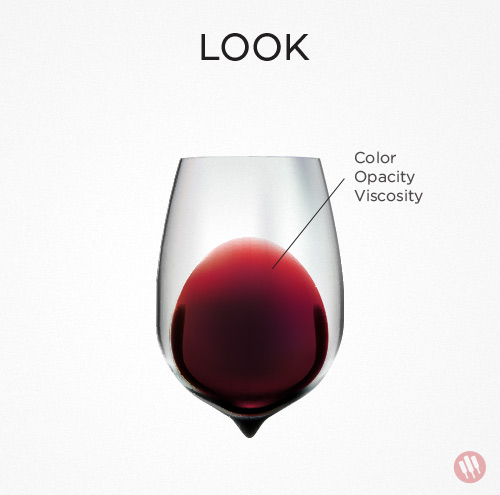

1. Look

Check out the color, opacity, and viscosity (wine legs). You don’t really need to spend more than five seconds on this step. Many clues about a wine are in its appearance, but unless you’re tasting blind, most of the answers that those clues provide will be found on the bottle (i.e. the vintage, ABV, and grape variety).

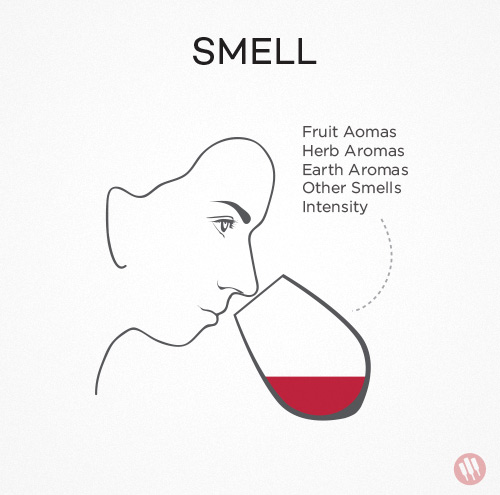

2. Smell

When you first start smelling wine, think big to small. Are there fruits? Think of broad categories first, i.e., citrus, orchard, or tropical fruits in whites or, when tasting reds, red, blue, or black fruits. Getting too specific or looking for one particular note can lead to frustration. Broadly, you can divide the nose of a wine into three primary categories:

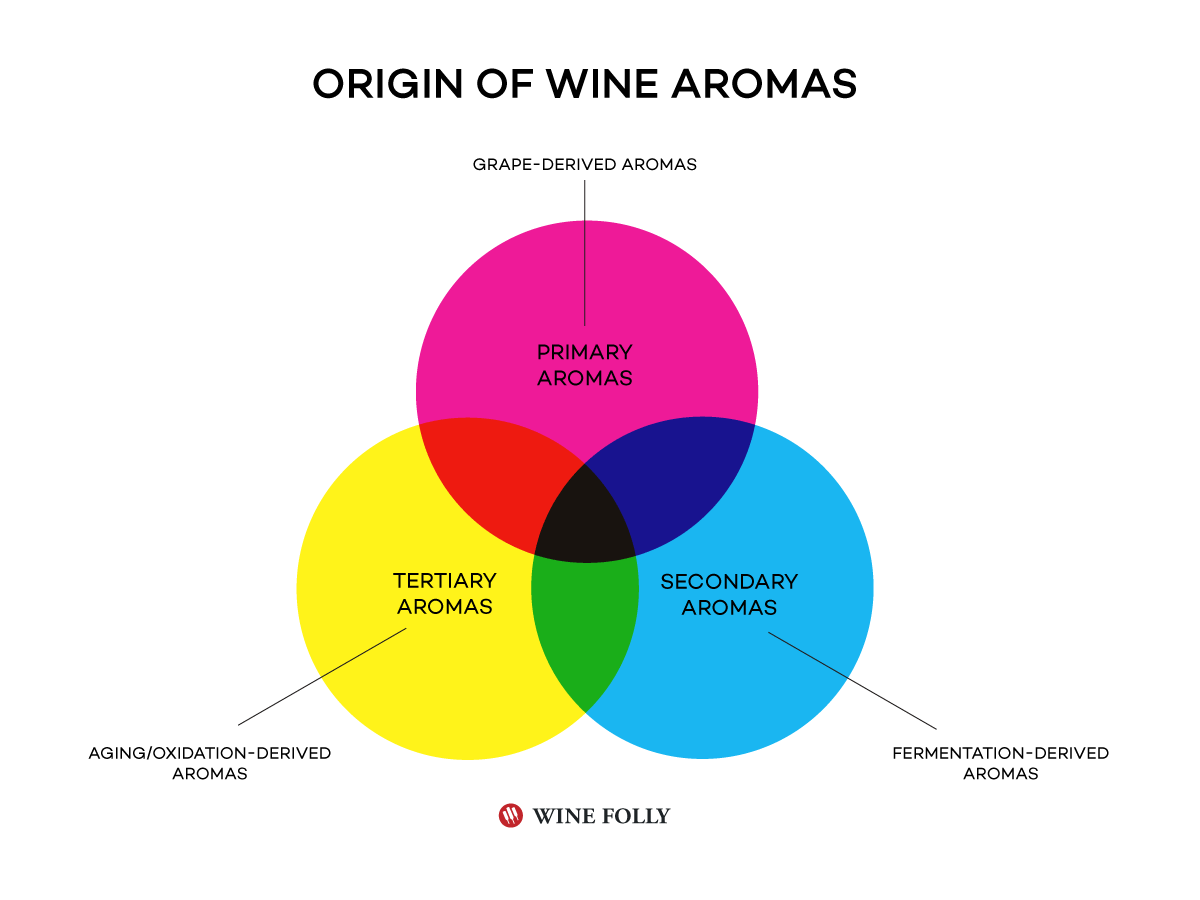

- Primary Aromas are grape-derivative and include fruits, herbs, and floral notes.

- Secondary Aromas come from winemaking practices. The most common aromas are yeast-derivative and easy to spot in white wines: cheese rind, nut husk (almond, peanut), or stale beer.

- Tertiary Aromas come from aging, usually in the bottle or possibly in oak. These aromas are mostly savory: roasted nuts, baking spices, vanilla, autumn leaves, old tobacco, cured leather, cedar, and even coconut.

3. Taste

We use our tongues to observe the wine, and once we swallow it, the aromas may change as we receive them retro-nasally.

- Taste: Our tongues can detect salty, sour, sweet, or bitter. All wines will have some sourness because grapes all inherently have some acid. This varies with climate and grape type. Some varieties have inherent bitterness (i.e. Pinot Grigio), manifesting as a sort of light, pleasant tonic-water-type flavor. Some white table wines have a small portion of their grape sugars retained, and this adds natural sweetness. You can’t ever smell sweetness since only your tongue can detect it. Lastly, very few wines have a salty quality, but in some rare instances, salty reds and whites exist.

- Texture: Your tongue can “touch” the wine and perceive its texture. Texture in wine relates to a few factors, but an increase in texture almost always happens in a higher-alcohol, riper wine. Ethanol gives a wine texture because we perceive it as “richer” than water. We also can detect tannin with our tongue, which is that sand-paper or tongue-depressor drying sensation in red wines.

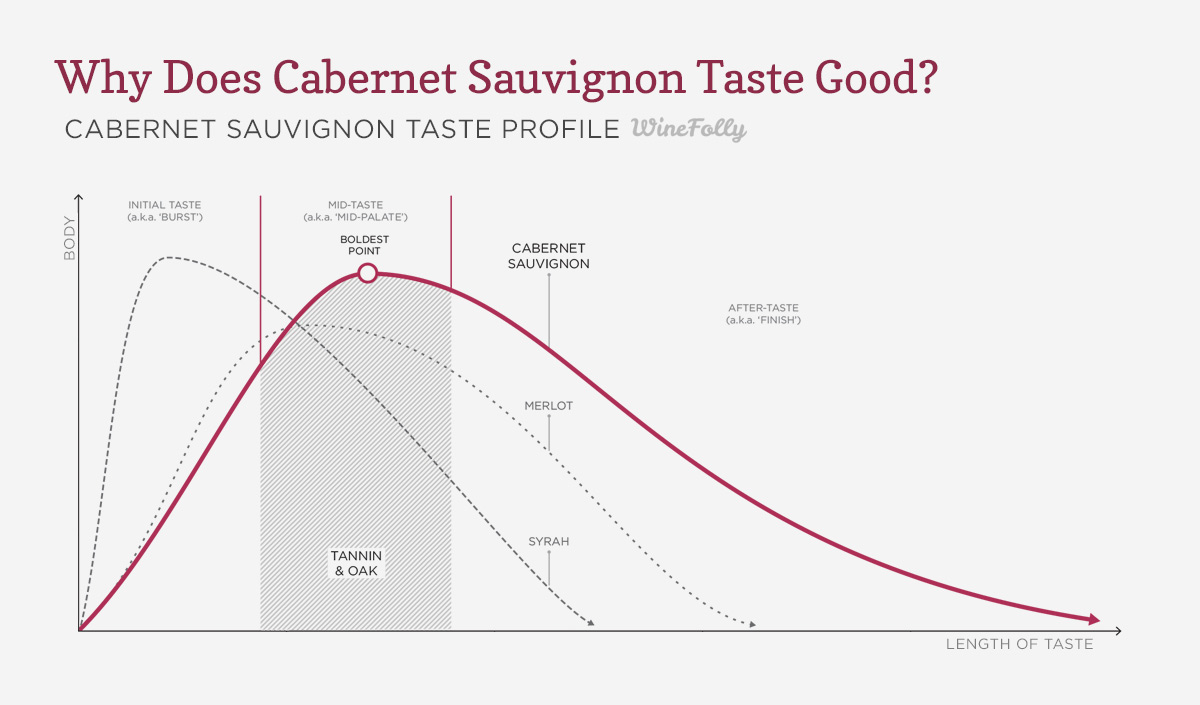

- Length: The taste of wine is also time-based; there is a beginning, middle (mid-palate), and end (finish). Ask yourself, how long will it take until the wine isn’t with you anymore?

4. Think

Does the wine taste like it’s in or out of balance (i.e. too acidic, alcoholic, or tannic)? Did you like the wine? Was this wine unique or unmemorable? Were there any shining or impressive characteristics?

Practice With The Video!

Prefer a quick overview? Grab a glass of wine and watch this 10-minute video on how to taste wine.

Helpful Tasting Tips

Getting past the “wine” smell: It can be challenging to move beyond the vinous flavor. A good technique is to alternate between small, short sniffs and slow, long sniffs.

Learn to Swirl: The act of swirling wine increases the number of aroma compounds released into the air. Watch a short video on how to swirl wine.

Find More Flavors When You Taste: Try coating your mouth with a larger sip of wine followed by several smaller sips to isolate and pick out flavors. Focus on one flavor at a time. Always think from broad-based flavors to more specific ones, i.e. the general “black fruits” to the more specific, “dark plum, roasted mulberry, or jammy blackberry.”

Improve Your Tasting Skills Faster: Comparing different wines in the same setting will help you improve your palate faster and make wine aromas more obvious. Get a flight of “tastes” at your local wine bar, join a local tasting group, or gather some friends to taste several wines all at once. You’ll be shocked by how much side-by-side of different varieties will show you!

Overloaded With Aromas? Neutralize your nose by sniffing your forearm.

How to Write Useful Tasting Notes: If you learn by doing, taking tasting notes will be very useful. Check out this useful technique on taking accurate tasting notes.

Step 1: Look

How to Judge the Look of a Wine: The color and opacity of wine can give you hints as to the approximate age, the potential grape varieties, the amount of acidity, alcohol, sugar, and even the potential climate (warm vs. cool) where the wine was grown.

Age: As white wines age, they tend to change color, becoming more yellow and brown, with an increase in overall pigment. Red wines tend to lose color, becoming more transparent as time passes.

Potential Grape Varieties: Here are some common hints you can look for in the color and rim variation.

- Nebbiolo and Grenache-based wines often have a translucent garnet or orange color on their rim, even in their youth.

- Pinot Noir will often have a true-red or true-ruby color, especially from cooler climates.

- Malbec will often have a magenta pink rim.

Alcohol and Sugar: Wine legs can tell us if the wine has high or low alcohol and/or high or low sugar. The thicker and more viscous the legs, the more alcohol or residual sugar is likely contained in the wine.

Step 2: Smell

How to Judge the Smell of Wine: Aromas in wine nearly give away everything about a wine, from grape variety, whether or not the wine has oak aging, where the wine is from, and how old the wine is. A trained nose and palate can pick all these details out.

Where Do Wine Aromas Actually Come From?

Aromas like “sweet Meyer lemon” and “pie crust” are aroma compounds called stereoisomers captured in our noses from evaporating alcohol. It’s like a scratch-and-sniff sticker. A single glass can have hundreds of different compounds, which is why people smell so many different things. It’s also easy to get lost in language since we all interpret individual aromas in related but slightly different ways. Your “sweet Meyer lemon” may be my “tangerine juice.” We’re both talking about the sweet citrus quality of the wine. We’re both correct – we’re just using slightly different words to express the idea.

Wine Aromas Fall into 3 Categories:

Primary Aromas: These aromas are derived from the type of grape and its growing climate. They include fruits, herbs, and floral notes, providing the most immediate impression of a wine. For instance, Barbera will often smell of licorice or anise, and this is because of compounds in Barbera grapes themselves, not because of a close encounter with a fennel bulb. Generally speaking, the fruit flavors in wine are primary aromas. If you’d like to see some examples, check out these articles:

- Identifying Fruit Flavors in Wine

- 6 Common Flower Flavors Found in Wine

- Red & Dark Fruit Flavors in Several Wine Varieties

Secondary Aromas: Secondary aromas come from the fermentation process (the yeast). A great example of this is the “sourdough” smell that you can find in Brut Champagne, which is sometimes described as “bready” or “yeasty.” Yeast aromas can also smell like old beer or cheese rind. Another common secondary aroma would be the yogurt or sour cream aroma that comes from malolactic fermentation. All in all, some of these aromas are quite bizarre.

Tertiary Aromas: Tertiary aromas (sometimes referred to as “bouquets”) come from aging wine. Aging aromas are attributed to oxidation, aging in oak, and/or aging in bottle over a period of time. The most common example of this is the “vanilla” aroma associated with wines aged in oak. Other more subtle examples of tertiary aromas are the nutty flavors in aged vintage Champagne. Often, tertiary aromas modify primary aromas, with the fresh fruit of a youthful wine changing to be more dried and concentrated as it develops.

Step 3: Taste

How to Judge the Taste of Wine: With practice, you could blind-taste a wine down to the style, region, and even possible vintage! Here are the details on what to pay attention to.

Sweetness:

The best way to sense sweetness is on the front of your tongue the first moment you taste a wine. Wines range from 0 grams per liter of residual sugar (g/L RS) to 450 g/L RS (which would be like syrup!). Sweet wines are traditionally made throughout France in Sauternes, Alsace, the Loire Valley, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Greece, and a few more! If you’re finding sweetness in a red wine that isn’t a dessert style (aka: not Port), then you have something kind of unique/strange on your hands!

- Dry Wines Most people would draw the line for dry wines at around 10 g/l of residual sugar, but the human threshold of perception is only 4 g/l. Most Brut Champagne will have around 6-9 g/l. Your average harmoniously sweet German Riesling has about 30 or 40 g/l.

- Acidity Matters Wines with high acidity taste less sweet than wines with low acidity because we generally perceive the relationship between sweetness and acidity, not the individual parts. Coke has 120 g/l but tastes relatively “dry” because of how much acidity it has! Coke’s really high acid is why you can also melt teeth and hair in it. Coke’s total acidity is way higher than any wine.

Acidity:

Acidity plays a major role in the overall profile of a wine because of the mouth-watering factor a wine has, which drives the wine’s refreshment factor. You can use these clues to determine if the wine is from a hot or cool climate, and even how long it might age.

Acidity Refers to pH: There are many types of acids in wine, but the overall acidity in wine is a pH measurement. Acidity is how sour a wine tastes. You generally perceive acidity as that mouthwatering, pucker-ing sensation in the back of your jaw. “Tart” or “zippy” are frequent descriptions of high-acid wines. The pH in wine ranges from 2.6, which is punishingly acidic, to about 4.9, barely detectable as tart, because it’s much closer to the neutral 7.0 measurement.

- Most wines range between 3 and 4 pH.

- Highly acidic wines are more tart and mouth-watering.

- High acidity can help you determine if a wine is from a cooler climate region or if the wine grapes were picked early.

- Low acid wines tend to taste smoother and creamier, with less mouth-watering qualities.

- Super low acid wines will taste flat or flabby.

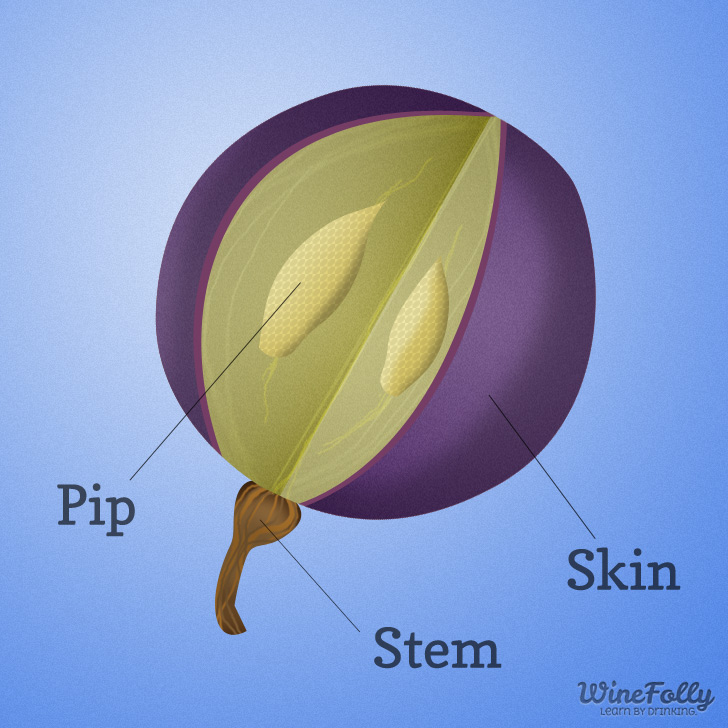

Tannin:

Tannin is a red wine characteristic and it can tell us the type of grape, if the wine was aged in oak, and how long the wine could age. You perceive tannin only on your palate and only with red wines and orange wines.

Tannin comes from 2 places: the skins and seeds of grapes or from oak aging. Every grape variety has a different inherent level of tannin, depending on its individual character. For example, Pinot Noir and Gamay have inherently low tannin levels, whereas Nebbiolo and Cabernet have very high levels.

- Grape Tannins Tannins from grape skins and seeds are typically more abrasive and can taste more green.

- Oak Tannins Tannins from oak will often taste more smooth and round. They typically hit your palate in the center of your tongue.

Tasting oak tannin versus grape tannin is extremely difficult, so don’t worry if you don’t get it right away.

Alcohol:

Alcohol can sometimes tell us the intensity of a wine and the ripeness of the grapes that went into making the wine.

- Alcohol level can add quite a bit of body and texture to wine.

- Alcohol ranges from 5% ABV – 16% ABV. A sub-11% ABV table wine usually means something with a little natural sweetness. Dry wines at 13.5% to 16% ABV are all going to be quite rich and intensely flavored. Fortified wines are 17-21% ABV.

- Alcohol level is directly correlated to the sweetness of the grapes before fermenting the wine. For this reason, lower ABV (sub-11%) wines will often have natural sweetness; their grape sugar wasn’t all turned into booze.

- Warmer growing regions produce riper grapes, which have the potential to make higher alcohol wines.

- Low vs. high alcohol wine Neither style is better than the other; it’s simply a characteristic of wine.

Body:

Body can give us clues to the type of wine, the region in which it was grown, and the possible use of oak aging. Body usually is directly related to alcohol, but think of body as how the wine “rests” on your palate. When you swish it in your mouth, does it feel like skim, 2%, or whole milk? That texture will roughly correspond with light, medium, and full-bodiedness in wine. Usually body will also correspond with alcohol, but various other processes like lees stirring, malolactic fermentation, oak aging, and residual sugar can all give a wine additional body and texture.

Step 4: Conclusion

This is your opportunity to sum up a wine. What was the overall profile of the wine? Fresh fruits with an acid-driven finish? Jammy fruits with oak and a broad, rich texture?

In a scenario when you are blind tasting a wine, you would use this moment to attempt to guess what the wine it is that you’re tasting. Try hosting your own private blind tasting to hone your skills.

By activating our brains when we taste, we alter how we consume. Overall, it is a very good thing.